(I was sick this week and will get back to finishing Loring next week. In the meantime, here is a brief essay I published years and years ago in Mpls-St. Paul Magazine.)

We’re headed for snow time again, so things will be back to normal again in my adopted Minneapolis, and I’m comfortable. On Saturday afternoons, friends telephone ahead, then trudge across the bridge from their neighborhood to ours. We drink hot chocolate and watch the flames in the fireplace. In a cold climate, the offer of a fire ranks with breaking bread, while people who are frequently snowbound develop, over endless winters, a desire to be left alone, or at least to be telephoned before they are visited.

Maybe I feel attracted to such an environment because once a very long time ago, at a time I felt especially dissatisfied and aimless, I rented a primitive cabin in the woods and tried going it alone. No running water. Wood heat. The nearest neighbor a half-mile away. I termed it my experiment in “intentional living.” Perhaps I would hoe beans in summer and record the warfare of ants. My plan was to get by as an odd-jobber, and, though my handiness was untested, I approached the prospect with confidence, guided by the happy image of the handyman with a liberal arts degree and a full bookshelf.

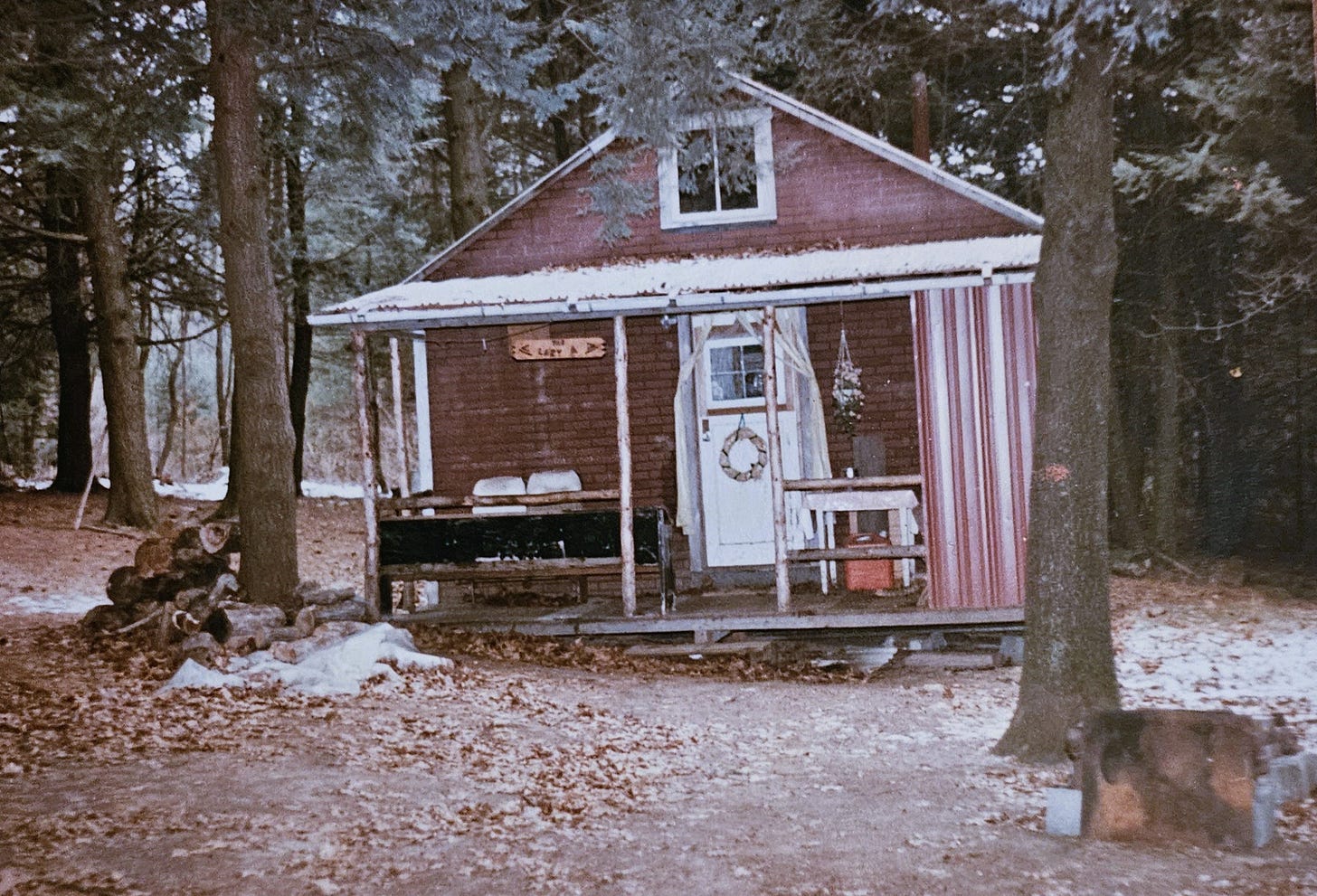

In early fall, I gathered my tools, a couple of battered antique chairs, warm work clothing, and my precious typewriter and books. I loaded them onto the bed of my baby blue ’55 Chevy pickup and drove out to Tadpole Road, where I would live. It was a room in the woods—four shingled walls, a wood stove, a tin roof, and a single bare light bulb. A woodshed leaned, exhausted, against a red oak a few steps from the porch. The outhouse stood doorless part way up the hill.

I moved in, stocked the woodshed, and found in a junk pile a lovely maple door with a full-length oval window. This I fit onto the outhouse. My landlord, Dick Fye, whose farm was a mile up the road, thought a picture window on a privy was the greatest joke since “intentional living.”

On the day of the first substantial snowfall in November my truck broke down, effectively putting me out of the handyman business. It needed rings, a valve job, money I didn’t have, skills I’ll never have.

More snow fell. I busied myself chopping wood, stuffing an odd collection of fiberglass scraps into the walls and stacking cornstalks around the cabin to insulate the foundation. The snow continued, covering all but one blue patch of the Chevy, weighing down the hemlock boughs, and silencing the woods around me. I grew a beard—my winter coat, Dick called it—and settled in, jobless and frightened.

But wasn’t this the point, to test myself stripped of the essentials? To go it alone? To drop out, needed by and needing no other person? Even inside the cabin I wore double layers of everything and a watch cap pulled over my ears. I boiled water for tea on the upright wood burner and blew on my cold fingers as I watched the jumping flames through the cracked stovetop. And I hauled my water on a shoulder yoke from a spring at the bottom of the hill.

My neighbors formed a woodcutting group, the Tadpole Firewood Corporation, Dick called it. They arranged to collect the barky slab-wood from a nearby sawmill. As a shareholder, I would contribute my labor. We watched out for one another. If a person needed firewood he got it, even if he couldn’t help out that day. We collected the slabs in pickup trucks, cut them into stove-length pieces on a circular saw rigged to Dick’s tractor, and then we delivered them together. My world now consisted of a neighborhood of farms. I hadn’t intended that, but I worked and socialized cheerfully.

An owl hooted each night from a tree behind my outhouse and was answered by another from across the frozen hollow. I listened every night. It was not an echo. Two paths cut through the deepening snow. One led across the hundred yards between my cabin and the road—at one end, a chair and a mug of hot chocolate; at the other, a parking space shoveled out for visiting friends. A second path led over a meandering staircase of packed snow down the steep, wooded hillside to the spring.

Dick used the visitor’s path often, right into mud time when I was ready to move back into town. “You know,” he told me that spring, “I don’t guess you would have made it without our help.”

“That’s true,” I said. “But remember, I’m the one who slept out here. I didn’t have a warm bed and running water..”

He saw my point, and I live now with his. No matter where we are we need those friends who trudge across the bridge from their neighborhood to ours. And in my memory of coming back up the meandering hillside path with my shoulder yoke and two full buckets of spring water it is always night. The trip is a delicate turning of the weight across my shoulders, a deft slide through low, treacherous branches. It requires strength and balance and finding your way, even in the dark.