Edgar Allen Poe, in his seminal essay on Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Twice Told Tales, writes that the “skillful literary artist” first conceives the “effect” he or she aims to have on the reader and then invents the incidents that will support that effect.

This is likely true of horror stories, which aim to leave you with a creepy feeling that will provide you with entertaining nightmares. Ah, ha! might very well be the effect intended in a detective story. Tears are the goal of a tearjerker. But what about stories that don’t fit into a neat genre?

Though I don’t pretend to know what was in the minds of Chekhov et al as they sat down to create their stories, I doubt that the effects created came about so neatly. I suspect that what came first was a character imagined or encountered, a story overheard or experienced. I suspect the “effect” grew out of the material, rather than the material lining up to serve a preconceived effect. I also suspect that a story’s money note, that moment at the end of the story when we feel moved in some way, came about as the writer, struggling through draft after draft, discovered the effect as if getting to the product of a line of addition. What is the sum (in this case, effect) of 13 plus 27 plus 32? Oh, 72! The incidents of the story add up to the effect. We discover the product by addition. This is certainly true for a reader, but I think it is also mostly true for the writer.

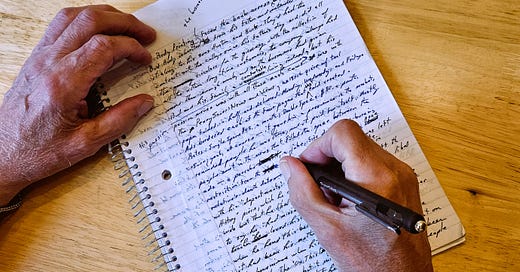

How we start, how we get an idea and make that idea into a rough draft, is fascinating, but what we do with the rough draft is, for me, the most interesting part of the writing process. It is during revision that you often discover what the story is really about. It is the part of the process where the story is most apt to reveal itself.

It’s also the longest part of the process.

The way that many of us were taught to write in school has left us with deadening misconceptions. The emphasis was on getting spelling, grammar, organization just right. No fooling around, folks. This is serious business. What we thought, our ideas or whimsy seemed to have not meant much. I must have heard, in the days I taught college composition classes, “You mean you want my opinion?” at least two hundred times.

Yes, I did.

The process of writing is a thinking-out process. We clarify our ideas and discover which ideas to send to the junk pile. In storywriting we revise to discover what we want to say, but also what the story wants to say, and that takes an intimacy with the characters and the situation that can only be achieved by spending a lot of time together. That means multiple drafts.

A simple heuristic for doing this is to isolate individual aspects of the story in a each time going through it. For example, after having read and tweaked a story a few times, you might want to pick through it looking only for places to change verb choices. Depending on your selection, you can begin changing the narrative tone with more whimsical or gloomy or sarcastic verbs. This goes for other parts of speech also.

Or you can isolate your search through the story to the dialogue of one character at a time, focusing on and enhancing that character’s speech patterns and mannerisms. Does the character swear a lot, use slang, speak pompously? What does the character want?

Or you could look at just one scene at a time and ask yourself how you might better express the miscommunication between the characters.

Or, looking at the scenes and remembering your reading of Chekhov, try your hand at adding that telling detail that will bring the picture into high relief. Nabokov said of Chekhov’s work, “One notes the magic of the trifles the author collects…” Try some magic.

Or you could look at the rhythm of your sentence structure.

Or … You get the idea.

Be imaginative. Do multiple reading of the draft, tweaking it each time, allowing the story to emerge as you do so. Sleep with it. Have an affair.

How do you know when you are finished? When you read through it and find nothing else you want to change.