“Often as I lay thus every word of the tale came to me quite clearly but when I got out of bed to write it down the words would not come.” Sherwood Anderson

We’ve all had those nights when we just knew we had it all right there in our imagination, but when we tried to put it on paper “the words would not come.”

For those of us who have caught the writer’s disease, this can be fatal. We end up talking—or dreaming—away our stories.

Back in the day, when I had a head full of dreams and no written stories to my name, and when my favorite uncle had a house in Key West, I went down there for New Year’s Eve with my friend Anne. We hung out with my uncle and his collection of pretty young men and made our own friends with a straight couple who had arrived on their fishing boat.

On New Year’s Eve, Anne went off with my uncle and his friends, curious to experience a “gay New Year’s.” Our fishing boat friends were in the throes of a major (and drunken) marital dispute. I just wanted to have a peaceful beer and not watch them fight, so I went down to Sloppy Joe’s, reputed to have been Hemingway’s favorite bar in town. Every school boy with the writer’s disease, no matter his age, has to go there if he finds himself in Key West. But it’s not a pilgrimage. It’s a symptom.

So there I am at the bar talking to a woman who lives on the island and in walks her new friend. He’s six feet tall, plus a couple inches, with a salt and pepper beard and a booming voice. His top two shirt buttons are open. Hairy chested, a drink in his hand, his feet planted as if he’s balancing on a pitching deck in a choppy sea. You can almost see the fishing lines disappearing into the waves behind him. And he loves Hemingway. Worships Hemingway. He tells me he’s a writer.

“Oh. I’d like to see your work,” I say, a polite comment.

“Not yet,” he tells me. He points to his head. “It’s all up here,” he says. “Every word. All I have to do is write it down.”

I thought, “Oh. A phony.” Everybody knows you have to actually put it on paper. The number of people who can just “write it down” is practically nil, exceptions that prove the rule.

But here’s the thing. Aside from papers for school, I hadn’t written more than a few lines myself. I had the disease as badly as he did. Having “every word” in your head is also a symptom, and, though I’d never said it out loud, as he had, I’d certainly deluded myself by thinking that some day I’d do just that, write it all down. No problem. It would all flow out the way I imagined it.

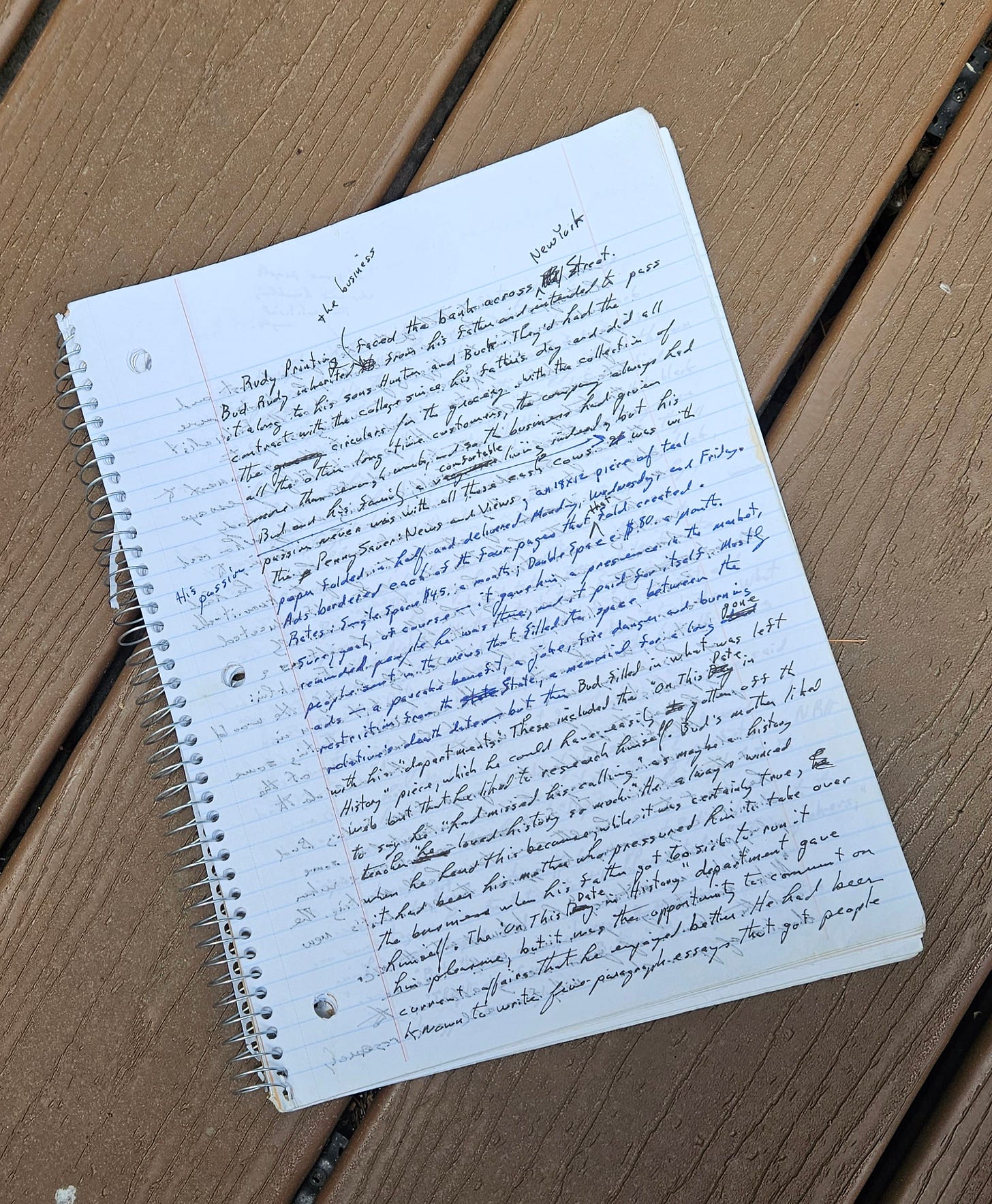

But here’s the other thing. You can’t write without suffering the messy rough draft. The old question—Do you want to be a writer or do you want to write?—is often answered by whether or not you complete the rough draft. Often, as Sherwood Anderson put it, the words will not come, meaning those beautiful words you had in your head. So you rough it out. You can’t get to the finished product without doing so. Nor can you get to what I think is the most interesting part of the writing process, revision.

Surprising, delighting yourself with what pops out of your mind and onto the page happens at all stages, the rough draft included. So does writing stupid, embarrassing stuff that you later delete or reshape into something not so stupid, and this stupidity is what we fear most and what keeps us from the rough draft. But you have to remind yourself that, though you may start that first draft with a brilliantly grand vision, you may finish far short of what you thought you had.

Nevertheless, now you actually have something to work with. Take a break. Treat yourself to a walk in the woods. Have a beer. You are started. Your story is no longer in your head. Instead, it looks like it’s becoming a real thing if you are willing to plant yourself in your chair and enter a conversation with that mess you made. Chances are it’s waiting to tell you something you never imagined would come out of yourself. It’s asking to be born.

Oh the Rough Draft!

I think what frightens us about writing is how it often wrestles us to where IT wants to go, rather than where we want it to go. Once it goes to paper, the perfect story we have in our heads gets flung in directions we couldn't have imagined. It's like approaching an unknown city at night, you see the bright lights, you know it's massive, but it's once you arrive in it that you realize how its shaped, you see all the bridges, the rivers, the parks, and beautiful eateries and shopping mauls.

I think the Rough Draft is that first tour of the new city.

And until you visit the eateries a second, a third time, see the bridges and buildings and parks, again and again, you still do not know the city.