Writers need alone hours to write and ruminate. They may also need walks or some other physical outlet, and everybody needs to keep connected with the important people in their lives. I had all of that. Things were coming together. Each morning I meditated and then wrote. After that I had my walk and my lunch. Prepping classes and grading papers, paying bills and, usually, making a call to a friend followed.

The chapters were mostly roughed out and I’d been over most of them a number of times, but I still wasn’t sure of how they cohered. A week here and a week there I focused only on one section or another. This is the longest and often the most exciting part of the writing process for me. I think of it as the discovery phase. The heart of the piece exists in there someplace, and I have to find it. I was getting closer to the time when I could start with the first chapter in the morning and work through to the end of the last before breaking off for the day.

This pattern held as long as I didn’t have a school to visit. Teaching evening classes posed no problem to the rhythm. School visits did, though.

But I needed them because I needed the money. One wants to establish and maintain a flow for a writing project, and coming back from a high energy week with kids I had to get my head back into a very different space. Sometimes getting back into the India manuscript came easy. Sometimes it didn’t. Sometimes a school week followed on the heels of a school week. Once, I had four in a row, all of them out-of-town. That meant a four-week drive all around Minnesota. A teaching marathon, staying in motels, eating in diners. I returned to my Loring Park apartment wrung out. The manuscript followed me with its eyes as I paced the floor and dawdled for the next week. When I returned to it, it didn’t want to give up any more of its secrets, kind of gave me the silent treatment, treated me like I’d been unfaithful.

Which, in fact, I had been. During those four weeks I had absolutely, positively fallen ass over teacups in love with doing school residency work. I’d figured out the contours of the residency I would conduct for the remainder of my professional life, and I had reinvented myself as a performing oral storyteller.

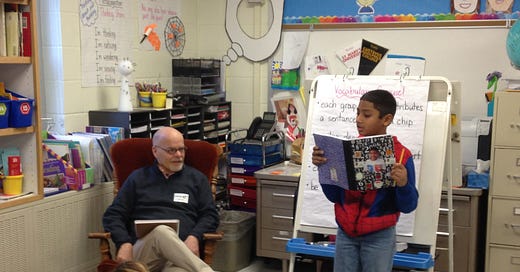

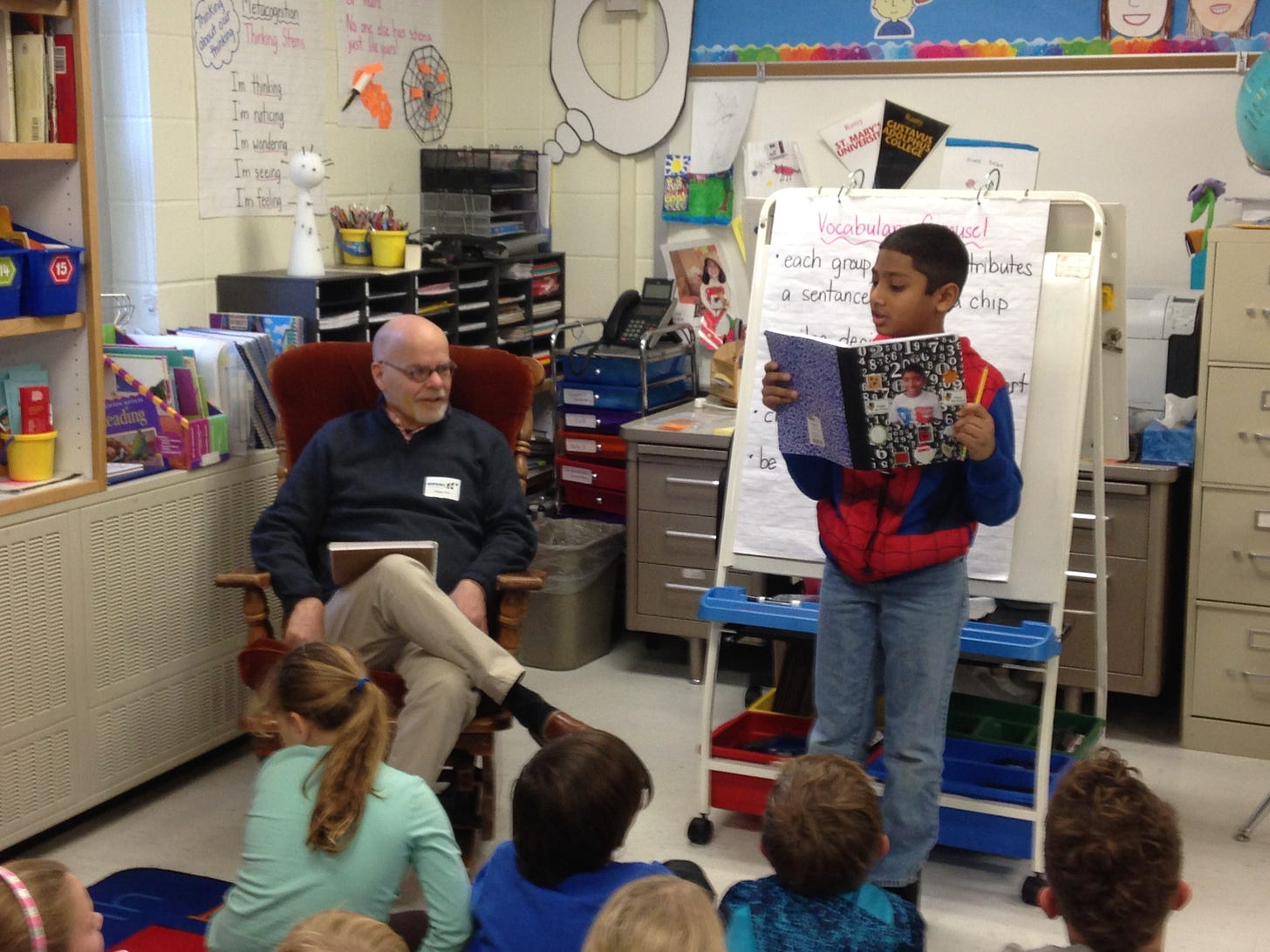

When I started out, I was just another writer visiting schools. What finally set me apart came one week during that around-the-state tour. A school in a small Minnesota town wanted me to work each day with the two sections of their fourth graders. The remaining two contact hours would be one-hour visits to all the other classes in the building. Everybody from kindergarten through sixth grade.

I’d been trying to figure out how to get kids to use more sensory detail in their stories, but hadn’t cracked the code yet. Nothing I tried seemed to make a difference. One piece of the answer is simple, of course. Remind them of the five senses. All kids learn that in kindergarten. I’d been doing just that in schools, but it still didn’t seem to make much difference. Everything I tried delivered blah results. One exercise I remember went something like: Describe a waterfall in the forest. Include all five of the senses. A boring assignment. Even then I knew that much. Predictively, the resulting “stories” were outstandingly nothingsvilles. Still, none of the other exercises yielded better results.

So, on a whim, literally while I was walking down the hall to my first class of the week, I decided that I would tell a story and include as much sensory detail as I could muster, then I’d ask the fourth graders to tell me what they saw, heard, felt, smelled, and tasted in my story. Okay, but what story would I tell them? Then, my hand on the classroom door knob, my mind went blank. No choice, though. I walked in and began introducing myself. I smiled down at them, they smiled back up at me, I told them a little about myself and asked if they liked stories. Well, of course they did. I told them that when we write stories we need to remember the five senses. “Can somebody tell me one of the five senses?” I asked.

Okay. We got those wonderful, magical, fantastical five senses on the board. “And now,” I told them, “I’m going to tell you a story, and I’m going to use all five of the senses in it. At the end, I’m going to ask you to tell me the senses I used.”

I still didn’t know what story I would tell them, but they were all in. I could see them shift in their seats, getting more comfortable to listen. At that moment I remembered my dad digging a hole in our back yard when I was five. I suspect the hole had something to do with the house’s plumbing, and I think I fell into it. So I started talking about that place where we had lived back then and about how I always wore bib overalls and my shoelaces were always untied. I made things up as I went along and I described our neighbors and found myself having a good time imitating them in a Pennsylvania Dutch voice.

But I didn’t know where the story was going. Off in my own weird dreamland, I suddenly looked down at the class. They all looked straight back to me, eyes alive, hands on desks, forward leaning bright faces. Oh, my God, Peters! I thought. This better be good or you are DEAD for the rest of this week!

Well. It was good. Can’t tell you how that happened, but it did.

I told the same story to the other fourth grade section and then to each classroom in the building, and the story got better and better with the telling. That’s how a story gets better, spoken or written. That’s the secret. How many times have I told that story over the years? How many tweaks have I made to it and to the way I introduce and conduct the lesson? I can’t count that high. When did cartooning become a part of the lesson? I honestly don’t remember.

But it’s the story that helps get me asked back to schools year after year, teaching story writing, telling stories, and listening to the stories kids make up.

I’ve been in love with school residency work all the way, adding stories to my repertoire as I’ve gone along, and there came a time, long after that residency, when walking into a classroom of fresh young faces actually saved my life.

But that’s another story. We’ll get to it eventually.