On my own now, I had rent to pay and a kitchen to keep supplied with noodles. Before going off to India, I had, in addition to writing, been conducting writing residencies in schools—K through 12—and teaching classes at an evening college. This had been a very, very part-time thing. I had had the luxury of making writing come first. But now, things had changed.

The school gig was especially rewarding. I did it through an arts organization in St. Paul called COMPAS that arranges for a variety of artists to do week-long residencies in schools all over the state. Painters, poets, playwrights, storytellers, even a clown. I’d gotten hooked up with COMPAS a year or so after moving to Minnesota when I won a prize for a story I’d published in a now-defunct local slick magazine called Twin Cities. I think they gave me $200. It couldn’t have been much more. Anyway, the story won a prize at a writing center and I was invited with other writers to spend a series of weekends meeting with visiting big shots. Robert Coover, Louise Erdrich, Maxine Hong Kingston are three of the names I remember.

The first meeting I was talking to one of the winners in poetry and asked how she made a living. She told me about COMPAS, but said the application deadline had been that morning. I was too late to apply to get on the roster. I went ahead and put together application materials anyway and slipped them under the office doors on a Sunday afternoon. Monday morning I called and said, “I’m the guy who left you something to read today. I hope you will consider me.” They took me on the very next day. Winning that prize and connecting with COMPAS changed my life. I have been teaching story writing in schools all over Minnesota since the day after showing up with my manila envelope and slipping it under the door,

By accident, I became a performing storyteller in the process and regularly use telling stories to motivate the kids and to show them how sensory detail, characterization, setting, scene, story form, etc., etc, etc. work, and I discovered also how we can use story to teach critical thinking skills like cause and effect, and implication-inference. Knowing these things, of course, makes us better readers as well as better writers. Something in me resonates with children, so to this day I happily pack up my things and drive to the far corners of Minnesota to teach all day, and then return to my motel room too tired to write or read. Once a week I wade through a 100 or so scrawled stories and write a quick, encouraging remark on it. As time went on, I’ve learned to put that remark inside a speech bubble floating out of the mouth of a very quickly drawn cartoon character. Dogs, cats, bald men with beards, dragons, people with funny noses and crazy ears. Whatever pops into my brain in the fifteen seconds it takes to draw it. These drawings and my stories, along with the excellent program I developed (yes, I am proud of it), have unsurprisingly endeared me to teachers and children alike and gotten me invited back year after year.

Out on my own now, without an understanding, generous spouse to support me, I began aggressively looking to visit many more schools. I absolutely love the kids and the work, but schools don’t get my writing done.

I also took on more teaching at the evening college, Metro State in St. Paul. This, too, was rewarding work. Though billed as a composition course that would prepare students for paper writing in other classes, I thought of my course and taught it as a course in the personal essay. Naked utility be damned. I asked for students to express their own opinions and explore their memories in short essays, and I did my best to respectfully challenge them to be clear and to dig deeper. I assigned reading for discussion ranging from Martin Luther King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” to E. B. White’s “Once More to the Lake,” along with pieces by the likes of Annie Dillard and James Baldwin.

My students were generally older, many returning to formal education after a major life crisis or after hitting a wall at work. I marveled at the growth in their ability to articulate their ideas from week one of the course to week ten. And students who simply took my course to check a box and move on to more important matters often found themselves becoming hungrier than they thought possible for intellectual engagement.

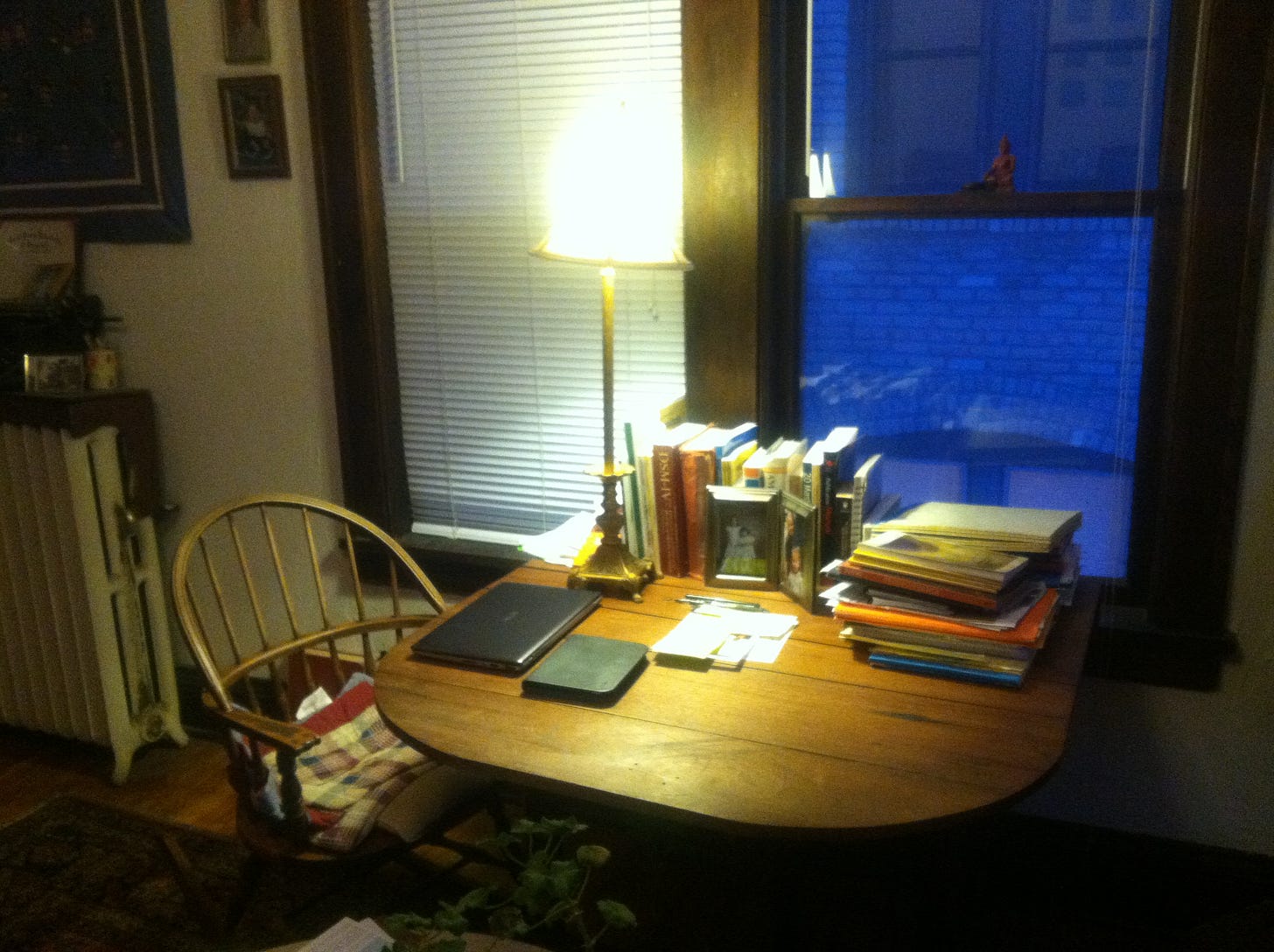

Teaching, no matter how rewarding, loaded me down with piles of papers to trudge through and mark up, lesson plans to create. My Metro State classes met once a week for three hours, so on class days I spent most of the day before class inventing 15-minute-by-15-minutes outlines of how we would spend those three hours, meeting the varied and extremely individualized needs of adult returning students. I should say that I love teaching and have always thrown myself into it. I should also acknowledge that I am a person of somewhat limited energy, with a need for alone/doing-nothing time every day, no exceptions.

My previous life as a married man with a wife working full time had given me the luxury of time to write. With that time, I’d written stories that won a few prizes and been in respectable journals. It had even given me the luxury of going off to India to write, first with a Minnesota State Arts Board grant and then on our own dime. Now faced with rent, health and car insurance, etc., etc., things suddenly weren’t so simple. I was far more apt to spend evenings at my desk marking up and grading personal essays than sitting under a floor lamp reading a book in my favorite chair.

And the India book was not getting written.