[This week begins my retirement from over thirty years of writing residencies in schools. As a small celebration, I’m re-posting this favorite story. Getting to work with kids and their writing was a blessing in my life. Enjoy.]

The Little Girl in the Hijab

Sometimes when you visit schools you meet kids you’ll never forget. You can read all the dry commentary you want about cognitive development and language acquisition or the resilience of the human spirit, but sometimes, if you are lucky enough, a kid will give it all to you, wrapped up in one happy moment.

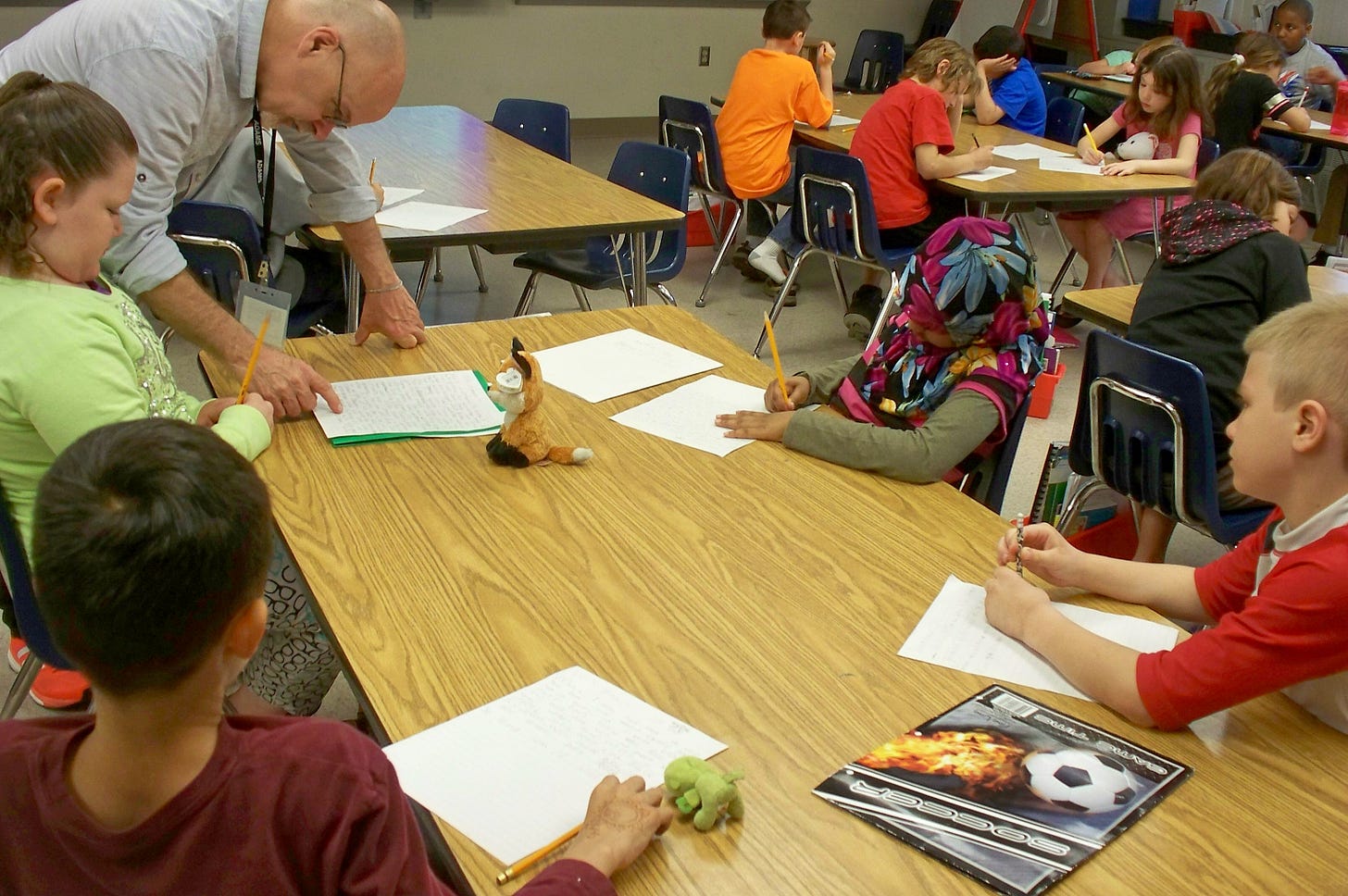

A few years ago I was asked to do a week-long writing residency in a first-ring suburban school. A large portion of the student population came from lower socio-economic conditions and first-generation immigrant families. The school wanted me to work with the third and fourth grades, probably my favorite age for residency work. Children in that age range are traversing the road from pure make-believe to the firmer ground of the concrete-operational developmental stage. They lap up a fun story and think I’m a brilliant artist when I make my mediocre cartoons on the board or on their papers.

One of my third grade sections had in it a little girl who, they told me, was newly arrived from Afghanistan. I didn’t know what part her family had played in the war there or what she had experienced or even what circumstances had brought her to Minnesota. In any case, she was a spirit. She wore a different, colorful hijab every day, her hair neatly tucked in. Not a strand showing. As her class traveled the hallways to and from art or gym or music, she fell right into the orderly single-file, cheerfully bouncing along with a huge smile and wide, liquid eyes, as if seeing the world for the very first time. Indeed, everything must have been new to her. When she saw someone she knew, me included, she lit up and waved. Her smile somehow grew and her eyes sent out invitations for fun and mischief.

She knew no English. Not a word, but she always seemed to know what was going on and what was expected of her. In class, she followed along with the lesson, attended to the stories I told to illustrate aspects of storymaking that I wanted the kids to try using in their own stories, and she worked right along with the other children during writing time. As I roamed the room helping and encouraging individual children, I naturally stopped by her table to look at what she was doing. I was taken aback.

She wrote random, Englishy-sounding words randomly around her paper. Wa might appear under the top right corner of the paper with suk at the bottom center, then nomte along the paper’s middle top. When I came back a little later, there would be four or five more attempts at English. Obij maybe. Or sunlip. The words would be scattered around her paper, and she would proudly point them out to me and smile. I tried gesture and made-up sign language to encourage her to make pictures if she wanted, a usual way I tried helping non-English-speaking students to express themselves. She smiled and shook her head yes, but went along making her Engfish, as I thought of it.

This went on all week—always in a beautiful, new hijab every day, never with a single strand of hair showing from under it, always with those big, shining eyes and the cheerful waves and smiles dancing down the hallway with her class. I thought her more wonderful and amusing each time I saw her. Her young teacher said she felt the same. This class was her first after student teaching. She was in love with it, especially with this lively little girl from the other side of the world.

By the end of the week, our little friend’s paper was covered with her made-up words. Her classmates had gotten to the end of their stories, and everybody had written their titles at the top of the first page. Some had even checked for capital letters and periods. Others had gone as far as to make an illustrated cover page. On Friday we would have a celebratory reading-aloud time.

That day, as always, I came into the room and reminded the class of what we were going to be doing and that they all needed to read over their stories now. They didn’t want to stumble over their words when they were reading to the class, I told them. Heads went down and lips moved silently above the papers. The little girl in the hijab joined in, her finger going from word to word. I gave them about five minutes, then sat myself down in a chair in the front of the room and invited them to come sit on the floor in front of me. Hands went up. Everybody wanted to be first to read. It was third grade, after all. The Afghan girl’s hand went up, too. In fact, it went up every time I asked who wanted to read next. Each time it went up, she waved it higher and with so much enthusiasm that I thought her arm would pop out of its socket. By the third or fourth reader, she added bouncing up and down as she waved her arm. The friendly smile never left her face.

At first, I thought I couldn’t call on her. Did she truly understand what she was volunteering for? Would she feel embarrassed once she got to her feet? I’d seen that happen with other children. Tears followed. Bodies crumpled. But she kept volunteering and time was running out. I looked to the teacher for some idea of what to do, but her eyes said that she was as worried as I was. So I called on the girl from Afghanistan. I shouldn’t have worried.

She popped out of her place and sailed off to retrieve her story. Like magic, she suddenly stood by my side. In a dramatic pause, she pulled herself to her full height with a long joyful breath, grinned at her classmates, and read her first word. She sent that word out into the upturned faces and let it hang out there for effect, then read a second word and allowed that to linger, too. All fidgeting, all squirming ceased. There might have been the sound of a locker opening and closing in the hallway, but there was not the least noise in our classroom. She read a third word. And then a fourth. They were coming faster now. We didn’t understand any of them, but they sounded vaguely familiar.

She went on. You could see the rapt concentration on the faces of her eight-year-old listeners. She smiled, almost laughed, at one point. At another, her chin fell to her chest and she nodded, as if to say, “Well, that happened, too,” but then pulled herself up straight again and continued with her usual smile. Something brave emerged from whatever narrative she was weaving for us, and we all understood she was telling us a story that she had lived. The class’s mouths hung open, their faces jutted forward, all eyes opened wide on her. The teacher sitting on a chair in the back wiped away tears. I steeled myself against doing the same, but finally had to remove my glasses and wipe my eyes as if I’d been reading too long late at night.

By then, she had stopped actually reading words from the page. I’d seen this before. The child wants to tell the story, but has not written it all yet, so only pretends to read. She went on for a long time with this. Eventually, we felt the story ending. The mood she had created with her made up Englishy words built to a climax and a satisfying resolution, like a piece of music, the lyrics of which we could only guess at.

The girl finished and the class burst into applause and cheers. The teacher’s cheeks glistened.

That was maybe ten years ago. She’d be eighteen or nineteen by now, very likely a popular top student headed for or early in college. I wonder where she is and if she remembers and if she would tell me what the story was that she told us that day when she was new to us and we to her.

Somehow, this beautiful story about a pure-hearted, luminous child, needs to reach a broader audience. Maybe as a short story, a play, or even a movie.

What an astonishing and moving experience that was! I desperately want you to find and reconnect with her, both to learn the secret of her story and to know what her path has been since then.