A friend recently recommended Annie Proulx to me. I’d read The Shipping News eons ago, and liked it well enough, and I’d seen Brokeback Mountain on the big screen, and vaguely understood it was based on one of her stories. I never looked her up, though. My friend swore she was brilliant and that I’d fall in love with her.

You might have thought I’d run right out and find a copy of her stories, but I hesitated. This friend has rather different tastes from mine. I’ve recommended authors to him from time to time and he’s kinda, sorta turned up his nose. “Yeah, I’ve read a little of that,” he’ll say, “but it leaves me cold. No thanks.” I figured we’re not on the same page. I’d just let it slide.

But then I was wandering through a bookstore one afternoon and Close Range, one of her story collections, almost jumped off the shelf at me.

A sign? Divine intervention?

I took it down and opened it to a random page near the back. “55 Miles to the Gas Pump,” I read. An intriguing title. I started reading. What is this? I thought. “Rancher Croom in handmade boots and filthy hat, that walleyed cattleman, stray hairs like curling fiddle string ends…” it began, gaining air speed and altitude for two paragraphs, ending in a single, tacked on, out there all by itself landing strip of a sentence: “When you live a long way out you make your own fun.” Wow. What was that?

So I read it again. Anything worthwhile can stand up to at least a second or third reading.

“55 Miles to the Gas Pump” has a seductive energy and weirdness that I like.

My friend, in introducing a different author to me some years before, had argued that art to be art needs to give you a “weird feeling.” Otherwise, it ain’t art. That was his test and he’s entitled to it. He’s a painter. But, really? I’d go as far as to say art needs to make you feel or think something. It has to move you in some way, but does it have to give you a “weird” feeling?

That argument aside, I read a few more of Annie Proulx’s stories, and I discovered something. The ones I liked the most started and ended as a poetry of landscape. One of my favorites, “People in Hell Just Want a Drink of Water,” begins like this: “You stand there, braced. Cloud shadows race over the bluff rock stacks as a projected film casting a queasy, mottled ground rash. The air hisses and it is no local breeze but the great harsh sweep of wind from the turning of the earth.”

Or try the opening paragraph to “The Bunchgrass Edge of the World”:

“The country appeared as empty ground, sagebrush, rabbitbrush, intricate sky, flocks of small birds like packs of cards thrown up in the air, and a faint track drifting toward the red-walled horizon. Graves were unmarked, fallen house timbers and corrals burned up in old campfires. Nothing much but weather and distance, the distance punctuated once in a while by ranch gates, and to the north the endless murmur and sun-flash of semis rolling along the interstate.”

Poetry.

Writing or reading, I like to remember what Irish writer Frank O’Connor said about the short story. He called it “the nearest thing I know to lyric poetry.” I bought that paperback copy of Close Range and gobbled down the stories in it for weeks. Proulx’s eye and ear, her selection of random, telling detail, her gift for the strangely dead-right image never fail her.

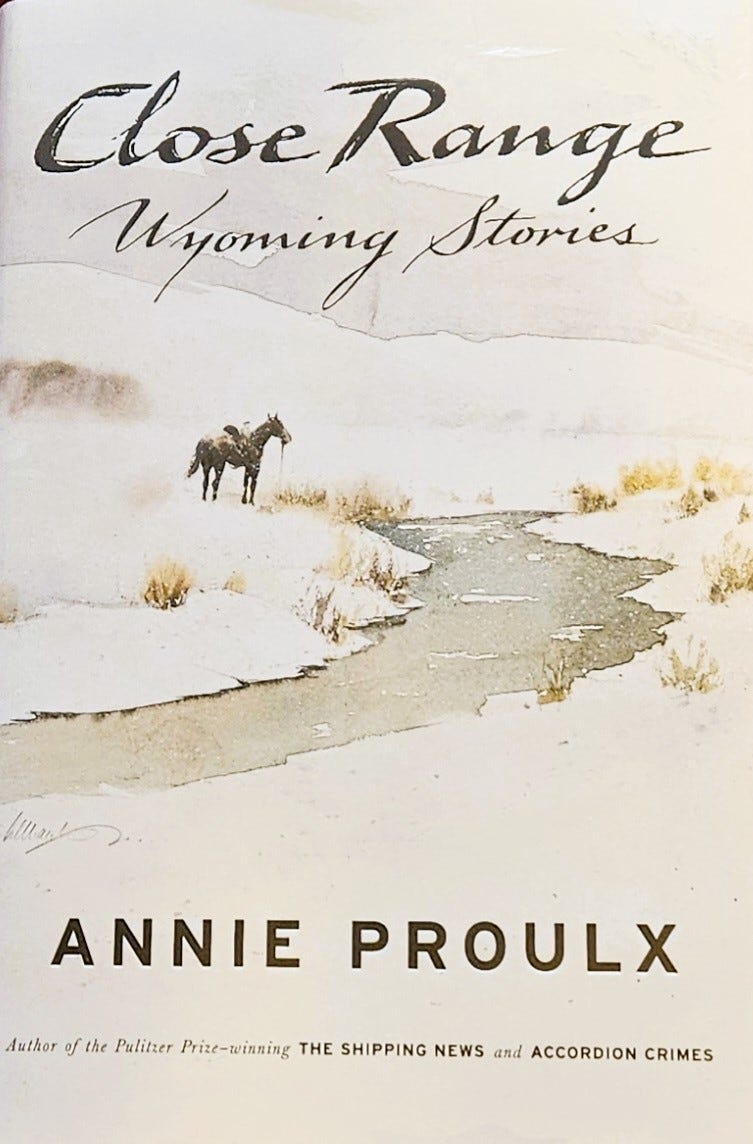

You might say I fell in love. I went online looking for her. In an interview with Charlie Rose she talked about the publication of Close Range. The painter William Matthews had told her at a conference that he wanted to illustrate her next book, but that’s something not done so much anymore, she told him. Nevertheless, she ran it by her publisher, who surprisingly went along with the idea. The result was a set of beautiful watercolors in the hardback first edition I found at Half Price Books.

These are dark, beautiful stories. Americana at its best. I highly recommend them to lovers of the short story. Savor their language, enter their world. You’ll thank me.